The Internet

More from technology

- The Internet

- ChatGPT: Artificial Intelligence possibilities for Uganda

- What is artificial intelligence

- What is a Website

- The Cost of Website Design, Development, and Hosting in Uganda: A Comprehensive Guide

- What is machine learning

- MacBook Review: The Laptop for Creatives and Professionals

- The Future of Education: How Artificial Intelligence is Changing the Way We Learn

- How to Create a Website That Aligns with Your Business Goals

- Tips to Improve Your E-commerce Website's Customer Experience

- 5 Ways to Improve Your E-commerce Website for Better Customer Experience

- New Technology Trends and Emerging Technologies in 2024

- 5 phones you should buy today instead of the Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra.

- Apple iPhone 16 hands-on review 2024

When you chat to somebody on the Net or send them an e-mail, do you ever stop to think how many different computers you are using in the process? There's the computer on your own desk, of course, and another one at the other end where the other person is sitting, ready to communicate with you. But in between your two machines, making communication between them possible, there are probably about a dozen other computers bridging the gap. Collectively, all the world's linked-up computers are called the Internet. How do they talk to one another? Let's take a closer look!

What is the Internet?

Global communication is easy now thanks to an intricately linked worldwide computer network that we call the Internet. In less than 20 years, the Internet has expanded to link up around 230 different nations. Even some of the world's poorest developing nations are now connected.

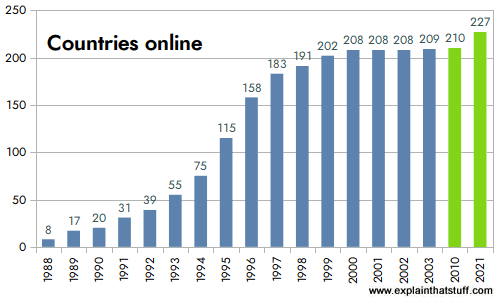

Chart: Countries online: In just over a decade, between 1988 and 2000, virtually every country in the world

went online. Although most countries are now "wired," that doesn't mean everyone is online in all those

countries, as you can see from the next chart, below.

Chart: Countries online: In just over a decade, between 1988 and 2000, virtually every country in the world

went online. Although most countries are now "wired," that doesn't mean everyone is online in all those

countries, as you can see from the next chart, below.

Lots of people use the word "Internet" to mean going online. Actually, the "Internet" is nothing more than the basic computer network. Think of it like the telephone network or the network of highways that criss-cross the world. Telephones and highways are networks, just like the Internet. The things you say on the telephone and the traffic that travels down roads run on "top" of the basic network. In much the same way, things like the World Wide Web (the information pages we can browse online), instant messaging chat programs, MP3 music downloading, and file sharing are all things that run on top of the basic computer network that we call the Internet.

The Internet is a collection of standalone computers (and computer networks in companies, schools, and colleges) all loosely linked together, mostly using the telephone network. The connections between the computers are a mixture of old-fashioned copper cables, fiber-optic cables (which send messages in pulses of light), wireless radio connections (which transmit information by radio. waves), and satellite links.

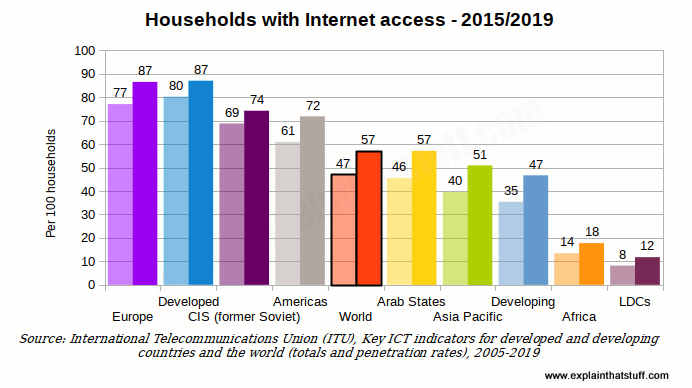

Chart: Internet use around the world: This chart compares the estimated percentage of households with Internet access for different world regions and economic groupings. For each region or grouping, the lighter bar on the left shows the percentage for 2015, while the darker bar shows 2019. Although there have clearly been dramatic improvements in all regions, there are still great disparities between the "richer" nations and the "poorer" ones. The world average, shown by the black-outlined orange center bars, is still only 57 out of 100 (just over half). Not surprisingly, richer nations are well to the left of the average and poorer ones well to the right. Source: Percentage of Individuals using the Internet 2000–2019 [XLS spreadsheet format], International Telecommunications Union, 2020.

In 2020, 92% of households have an internet connection, an increase of one percentage point since 2019. Data for 2020 indicates that fixed broadband is the most common type of internet access in the household (85% compared with 42% using mobile broadband). Note that more than one type of internet connection may be used in households.

In 2021, 93% of households have an internet connection, an increase of one percentage point since 2020. Household internet connectivity was highest for the Dublin region (96%), In 2021, almost all households with dependent children have internet access. This compares with just 79% of households comprised of one adult with no dependent children

What does the Internet do?

The Internet has one very simple job: to move computerized information (known as data) from one place to another. That's it! The machines that make up the Internet treat all the information they handle in exactly the same way. In this respect, the Internet works a bit like the postal service. Letters are simply passed from one place to another, no matter who they are from or what messages they contain. The job of the mail service is to move letters from place to place, not to worry about why people are writing letters in the first place; the same applies to the Internet.

Just like the mail service, the Internet's simplicity means it can handle many different kinds of information helping people to do many different jobs. It's not specialized to handle emails, Web pages, chat messages, or anything else: all information is handled equally and passed on in exactly the same way. Because the Internet is so simply designed, people can easily use it to run new "applications"—new things that run on top of the basic computer network. That's why, when two European inventors developed Skype, a way of making telephone calls over the Net, they just had to write a program that could turn speech into Internet data and back again. No-one had to rebuild the entire Internet to make Skype possible.

How does Internet data move?

Circuit switchingMuch of the Internet runs on the ordinary public telephone network—but there's a big difference between how a telephone call works and how the Internet carries data. If you ring a friend, your telephone opens a direct connection (or circuit) between your home and theirs. If you had a big map of the worldwide telephone system (and it would be a really big map!), you could theoretically mark a direct line, running along lots of miles of cable, all the way from your phone to the phone in your friend's house. For as long as you're on the phone, that circuit stays permanently open between your two phones. This way of linking phones together is called circuit switching. In the old days, when you made a call, someone sitting at a "switchboard" (literally, a board made of wood with wires and sockets all over it) pulled wires in and out to make a temporary circuits that connected one home to another. Now the circuit switching is done automatically by an electronic telephone exchange.

If you think about it, circuit switching is a really inefficient way to use a network. All the time you're connected to your friend's house, no-one else can get through to either of you by phone. (Imagine being on your computer, typing an email for an hour or more—and no-one being able to email you while you were doing so.) Suppose you talk very slowly on the phone, leave long gaps of silence, or go off to make a cup of coffee. Even though you're not actually sending information down the line, the circuit is still connected—and still blocking other people from using it.

Packet switchingThe Internet could, theoretically, work by circuit switching—and some parts of it still do. If you have a traditional "dialup" connection to the Net (where your computer dials a telephone number to reach your Internet service provider in what's effectively an ordinary phone call), you're using circuit switching to go online. You'll know how maddeningly inefficient this can be. No-one can phone you while you're online; you'll be billed for every second you stay on the Net; and your Net connection will work relatively slowly.

Most data moves over the Internet in a completely different way called packet switching. Suppose you send an email to someone in China. Instead of opening up a long and convoluted circuit between your home and China and sending your email down it all in one go, the email is broken up into tiny pieces called packets. Each one is tagged with its ultimate destination and allowed to travel separately. In theory, all the packets could travel by totally different routes. When they reach their ultimate destination, they are reassembled to make an email again.

Packet switching is much more efficient than circuit switching. You don't have to have a permanent connection between the two places that are communicating, for a start, so you're not blocking an entire chunk of the network each time you send a message. Many people can use the network at the same time and since the packets can flow by many different routes, depending on which ones are quietest or busiest, the whole network is used more evenly—which makes for quicker and more efficient communication all round.

How packet switching works

What is circuit switching?

Picture: Circuit switching is like moving your house slowly, all in one go, along a fixed route between two places.

Suppose you want to move home from the United States to Africa and you decide to take your whole house with you—not just the contents, but the building too! Imagine the nightmare of trying to haul a house from one side of the world to the other. You'd need to plan a route very carefully in advance. You'd need roads to be closed so your house could squeeze down them on the back of a gigantic truck. You'd also need to book a special ship to cross the ocean. The whole thing would be slow and difficult and the slightest problem en-route could slow you down for days. You'd also be slowing down all the other people trying to travel at the same time. Circuit switching is a bit like this. It's how a phone call works.What is packet switching?

Picture: Packet switching is like breaking your house into lots of bits and mailing them in separate packets. Because the pieces travel separately, in parallel, they usually go more quickly and make better overall use of the network.

Is there a better way? Well, what if you dismantled your home instead, numbered all the bricks, put each one in an envelope, and mailed them separately to Africa? All those bricks could travel by separate routes. Some might go by ship; some might go by air. Some might travel quickly; others slowly. But you don't actually care. All that matters to you is that the bricks arrive at the other end, one way or another. Then you can simply put them back together again to recreate your house. Mailing the bricks wouldn't stop other people mailing things and wouldn't clog up the roads, seas, or airways. Because the bricks could be traveling "in parallel," over many separate routes at the same time, they'd probably arrive much quicker. This is how packet switching works. When you send an email or browse the Web, the data you send is split up into lots of packets that travel separately over the Internet.

What are "clients" and "servers"?

There are hundreds of millions of computers on the Net, but they don't all do exactly the same thing. Some of them are like electronic filing cabinets that simply store information and pass it on when requested. These machines are called servers. Machines that hold ordinary documents are called file servers; ones that hold people's mail are called mail servers; and the ones that hold Web pages are Web servers. There are tens of millions of servers on the Internet.

A computer that gets information from a server is called a client. When your computer connects over the Internet to a mail server at your ISP (Internet Service Provider) so you can read your messages, your computer is the client and the ISP computer is the server. There are far more clients on the Internet than servers—probably getting on for a billion by now!

When two computers on the Internet swap information back and forth on a more-or-less equal basis, they are known as peers. If you use an instant messaging program to chat to a friend, and you start swapping party photos back and forth, you're taking part in what's called peer-to-peer (P2P) communication. In P2P, the machines involved sometimes act as clients and sometimes as servers. For example, if you send a photo to your friend, your computer is the server (supplying the photo) and the friend's computer is the client (accessing the photo). If your friend sends you a photo in return, the two computers swap over roles.

Apart from clients and servers, the Internet is also made up of intermediate computers called routers, whose job is really just to make connections between different systems. If you have several computers at home or school, you probably have a single router that connects them all to the Internet. The router is like the mailbox on the end of your street: it's your single point of entry to the worldwide network.

How the Net really works: TCP/IP and DNS

The real Internet doesn't involve moving home with the help of envelopes—and the information that flows back and forth can't be controlled by people like you or me. That's probably just as well given how much data flows over the Net each day—roughly 3 billion emails and a huge amount of traffic downloaded from the world's 250 million websites by its 2 billion users. If everything is sent by packet-sharing, and no-one really controls it, how does that vast mass of data ever reach its destination without getting lost?

The answer is called TCP/IP, which stands for Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol. It's the Internet's fundamental "control system" and it's really two systems in one. In the computer world, a "protocol" is simply a standard way of doing things—a tried and trusted method that everybody follows to ensure things get done properly. So what do TCP and IP actually do?

Internet Protocol (IP) is simply the Internet's addressing system. All the machines on the Internet—yours, mine, and everyone else's—are identified by an Internet Protocol (IP) address that takes the form of a series of digits separated by dots or colons. If all the machines have numeric addresses, every machine knows exactly how (and where) to contact every other machine. When it comes to websites, we usually refer to them by easy-to-remember names (like www.explainthatstuff.com) rather than their actual IP addresses—and there's a relatively simple system called DNS (Domain Name System) that enables a computer to look up the IP address for any given website. In the original version of IP, known as IPv4, addresses consisted of four pairs of digits, such as 12.34.56.78 or 123.255.212.55, but the rapid growth in Internet use meant that all possible addresses were used up by January 2011. That has prompted the introduction of a new IP system with more addresses, which is known as IPv6, where each address is much longer and looks something like this: 123a:b716:7291:0da2:912c:0321:0ffe:1da2.

The other part of the control system, Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), sorts out how packets of data move back and forth between one computer (in other words, one IP address) and another. It's TCP that figures out how to get the data from the source to the destination, arranging for it to be broken into packets, transmitted, resent if they get lost, and reassembled into the correct order at the other end.

A brief history of the Internet

Precursors- 1844: Samuel Morse transmits the first electric telegraph message, eventually making it possible for people to send messages around the world in a matter of minutes.

- 1876: Alexander Graham Bell (and various rivals) develop the telephone.

- 1940: George Stibitz accesses a computer in New York using a teletype (remote terminal) in New Hampshire, connected over a telephone line.

- 1945: Vannevar Bush, a US government scientist, publishes a paper called As We May Think, anticipating the development of the World Wide Web by half a century.

- 1958: Modern modems are developed at Bell Labs. Within a few years, AT&T and Bell begin selling them commercially for use on the public telephone system.

- 1964: Paul Baran, a researcher at RAND, invents the basic concept of computers communicating by sending "message blocks" (small packets of data); Welsh physicist Donald Davies has a very similar idea and coins the name "packet switching," which sticks.

- 1963: J.C.R. Licklider envisages a network that can link people and user-friendly computers together.

- 1964: Larry Roberts, a US computer scientist, experiments with connecting computers over long distances.

- 1960s: Ted Nelson invents hypertext, a way of linking together separate documents that eventually becomes a key part of the World Wide Web.

- 1966: Inspired by the work of Licklider, Bob Taylor of the US government's Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) hires Larry Roberts to begin developing a national computer network.

- 1969: The ARPANET computer network is launched, initially linking together four scientific institutions in California and Utah.

1970s: The modern Internet appears

1970s: The modern Internet appears

- 1971: Ray Tomlinson sends the first email, introducing the @ sign as a way of separating a user's name from the name of the computer where their mail is stored.

- 1973: Bob Metcalfe invents Ethernet, a convenient way of linking computers and peripherals (things like printers) on a local network.

- 1974: Vinton Cerf and Bob Kahn write an influential paper describing how computers linked on a network they called an "internet" could send messages via packet switching, using a protocol (set of formal rules) called TCP (Transmission Control Protocol).

- 1978: TCP is improved by adding the concept of computer addresses (Internet Protocol or IP addresses) to which Internet traffic can be routed. This lays the foundation of TCP/IP, the basis of the modern Internet.

- 1978: Ward Christensen sets up Computerized Bulletin Board System (a forerunner of topic-based Internet forums, groups, and chat rooms) so computer hobbyists can swap information.

- >1983: TCP/IP is officially adopted as the standard way in which Internet computers will communicate.

- 1982–1984: DNS (Domain Name System) is developed, allowing people to refer to unfriendly IP addresses (12.34.56.78) with friendly and memorable names (like google.com).

- 1986: The US National Science Foundation (NSF) creates its own network, NSFnet, allowing universities to piggyback onto the ARPANET's growing infrastructure.

- 1988: Finnish computer scientist Jarkko Oikarinen invents IRC (Internet Relay Chat), which allows people to create "rooms" where they can talk about topics in real-time with like-minded online friends.

- 1989: The Peapod grocery store pioneers online grocery shopping and  e-commerce.

- 1989: Tim Berners-Lee invents the World Wide Web at CERN, the European particle physics laboratory in Switzerland. It owes a considerable debt to the earlier work of Ted Nelson and Vannevar Bush.

1990s: The Web takes off

1990s: The Web takes off

- 1993: Marc Andreessen writes Mosaic, the first user-friendly web browser, which later evolves into Netscape and Mozilla.

- 1993: Oliver McBryan develops the World Wide Web Worm, one of the first search engines.

- 1994: People soon find they need help navigating the fast-growing World Wide Web. Brian Pinkerton writes WebCrawler, a more sophisticated search engine and Jerry Yang and David Filo launch Yahoo!, a directory of websites organized in an easy-to-use, tree-like hierarchy.

- 1995: E-commerce properly begins when Jeff Bezos founds Amazon.com and Pierre Omidyar sets up eBay.

- 1996: ICQ becomes the first user-friendly instant messaging (IM) system on the Internet.

- 1997: Jorn Barger publishes the first blog (web-log).

- 1998: Larry Page and Sergey Brin develop a search engine called BackRub that they quickly decide to rename Google.

- 1999: Kevin Ashton conceives the idea that everyday objects, and not just computers, could be part of the Internet. This idea is now known as the Internet of Things.

- 2003: Virtually every country in the world is now connected to the Internet.

- 2004: Harvard student Mark Zuckerberg revolutionizes social networking with Facebook, an easy-to-use website that connects people with their friends.

- 2006: Jack Dorsey and Evan Williams found Twitter, an even simpler "microblogging" site where people share their thoughts and observations in off-the-cuff, 140-character status messages.

- 2017: Russian president Vladimir Putin approves a plan to create a private alternative to the Internet to counter the historic dominance of the (traditional) Internet by the United States.